Environmental Degradation of Architectural Metals:

Mechanisms, Failure Patterns, and Technical Lessons from the

Restoration of Yaquina Bay Lighthouse

Architectural metals have long served as both the functional and expressive components of America’s most enduring structures—from monumental civic buildings to remote coastal lighthouses. Yet in the absence of recurring maintenance, these same metals are highly vulnerable to deterioration driven by moisture, pollutants, chlorides, and thermal cycling.

The following article synthesizes broader environmental science with the specific findings from the Yaquina restoration, placing the project within the context of nationally recognized guidance such as the NPS Historic Lighthouse Preservation Handbook.

Environmental Drivers of Metal Deterioration

Metal deterioration in historic buildings is rarely the result of a single factor. Rather, it is driven by overlapping stressors that accelerate one another. For coastal structures, lighthouses in particular, three forces dominate.

1. Salt Aerosols and Chloride Deposition

Salt-laden air is the defining environmental challenge for coastal metal assemblies. Airborne chlorides:

- Deposit onto metal surfaces

- Absorb atmospheric moisture and form a thin electrolyte film

- Initiate localized pitting

- Undermine coatings from beneath

- Migrate into joints and bolt penetrations

Because salt remains hygroscopic, corrosion continues even during dry weather.

This condition matches what the NPS identifies as the primary cause of metal failure in coastal lighthouses.

At Yaquina, chloride-driven corrosion produced:

- section loss at cast iron interfaces

- accelerated pitting at horizontal surfaces

- widespread deterioration at mechanical attachment points

- deformation in thin ornamental elements

2. Thermal Cycling & Freeze–Thaw Expansion

Rapid temperature changes drive expansion and contraction of both metals and entrapped moisture. Freeze–thaw action exerts significant force, widening cracks and rupturing coatings.

At Yaquina, this manifested as:

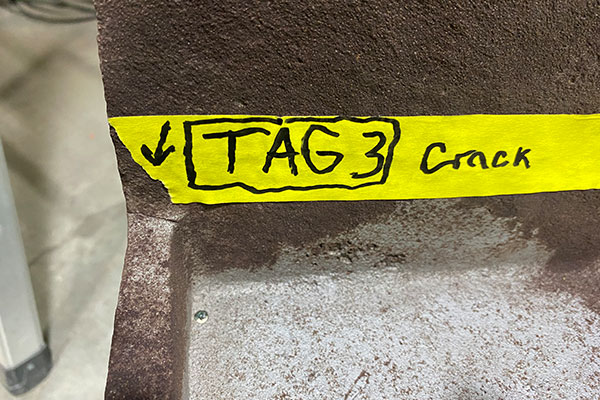

- crack propagation radiating from bolt holes

- delamination of original coating systems

- deformation of panels under repetitive thermal stress

The NPS notes that lantern rooms, being both highly exposed and assembled from many attachment interfaces, are particularly vulnerable to this type of cyclical failure.

3. Pollutants, Acid Deposition, and Galvanic Activity

Sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and industrial particulates produce acidic moisture that destabilizes natural patinas and accelerates oxidation. Where ferrous and non-ferrous metals meet, galvanic corrosion becomes a secondary threat.

At Yaquina, mixed-metal assemblies (cast iron, steel, bronze) showed deterioration patterns consistent with both acidic deposition and galvanic activity, particularly where moisture was trapped against dissimilar metals.

Early Indicators of Metal Failure

- Blistering or lifting of paint

- Rust “bloom” at fasteners

- Crack lines radiating from bolt holes

- Powdering patina on bronze

- Deformation or misalignment of components

- Staining on adjacent surfaces

These early indicators typically suggest more significant deterioration concealed beneath coatings.

Corrosion Mechanisms

Oxidation — metal reacts with oxygen and moisture

Electrochemical corrosion — salts create an active electrolytic field

Crevice corrosion — moisture trapped in interfaces accelerates attack

Underfilm corrosion — coatings fail from the substrate outward

Case Study: Technical Breakdown of the

Yaquina Bay Lantern Room Restoration

Initial Documentation and Controlled Disassembly

Upon mobilization, the lantern structure was comprehensively documented, photographed, and cataloged. Disassembly occurred methodically, with every component tagged and sorted according to material, function, and location. This controlled approach ensured traceability and preserved the ability to reconstruct assemblies accurately.

Blasting and Environmental Control

All parts were abrasive-blasted to remove coatings and corrosion products. Components were then stored in an environmentally controlled facility to prevent flash rusting and contamination, an essential step given the chloride content normally present on coastal metals.

Component Evaluation

Each piece was inspected for:

- cracks

- corrosion and pitting

- casting inclusions

- section loss

- dimensional irregularities

The evaluation confirmed advanced environmental deterioration consistent with long-term exposure.

Findings and Interventions by Component Type

Window Trim

All original window trim was deemed irreparable due to extensive section loss and deformation. Replacements were patterned from the historic profiles and recast to match original geometry and detailing.

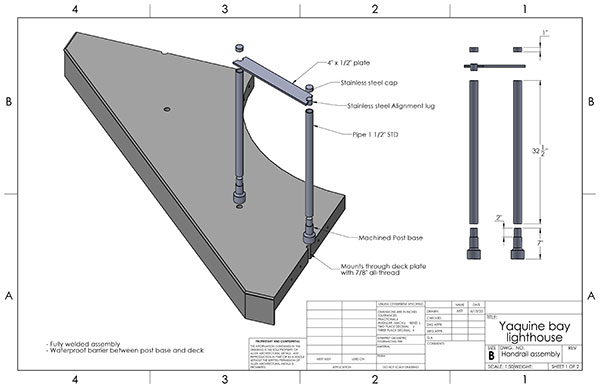

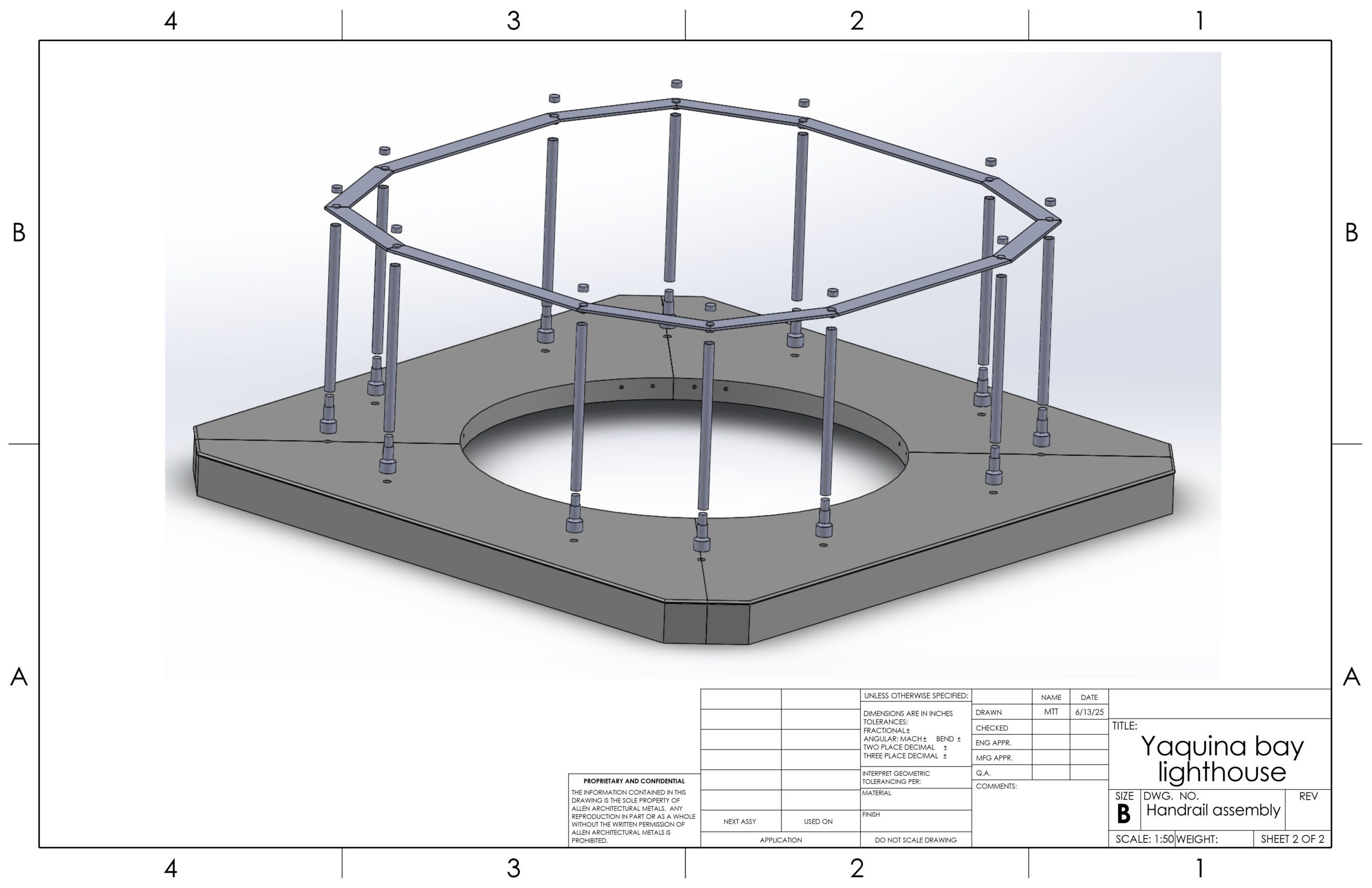

Handrails

Existing handrails were both structurally compromised and inconsistent with original design intent. New stainless-steel handrails, fabricated by Allen Architectural Metals, replicated the historic configuration while offering improved durability.

Cracks & Structural Failures in Panels

Cracks were found at nearly every mechanical attachment point, excluding only the parapet walls and window mullions. Notably:

- Roof and deck panels exhibited stress cracks radiating from bolt penetrations.

- Two roof panels displayed full-length cracks discovered after blasting.

- One panel fully separated once surface coatings were removed.

These conditions matched the deterioration pathways documented in the NPS Lighthouse Preservation Handbook, particularly those associated with thermal stress and moisture intrusion.

Weld Repairs and Infill Strategy

Cracks were addressed using a consistent, conservation-aligned methodology:

- V-Groove Preparation

Each crack was ground into a “V” profile to ensure adequate weld penetration. - Weld Repair

Certified personnel welded along the entire crack length using compatible filler materials. - Surface Restoration

Welds were ground flush to restore original profiles and maintain dimensional accuracy. - Material Patching

Areas of significant section loss were infilled with A36 steel, welded, and finished using the same method.

This approach aligns with preservation engineering best practices—retain original material wherever feasible, reinforce where possible, replace where necessary.

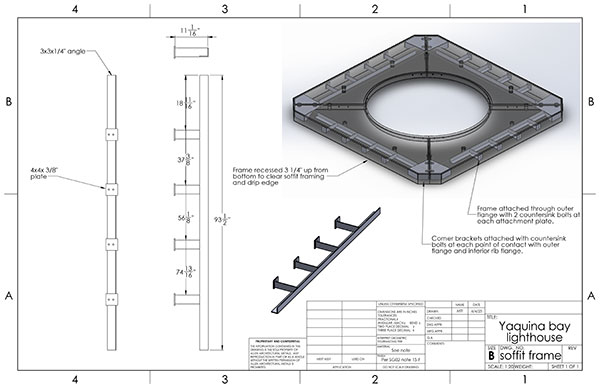

New Structural and Support Components

At the client’s request, AAM designed and fabricated:

- A soffit-mount frame, and

- Support weldments at the deck plate corners

Design intent and dimensional criteria were developed in coordination with PacTec.

These additions provide a robust structural platform while respecting the historic lantern geometry.

Coating System and Assembly

Once repairs were complete:

- Components were primed per specification using corrosion-resistant products suitable for high-chloride environments.

- Finish coats were applied to required film thickness.

- Assembly utilized new stainless steel mechanical hardware.

- Sealant was applied at all joints per specification.

- New glazing was installed, each pane etched with its manufacturing date for future documentation.

The fully assembled structure was then resealed and final-coated.

deckplate before

deckplate after

roof before

roof after

before

after

Before & After Technical Summary

Before Restoration

- Chloride-induced restoration

- Widespread cracking at bolt penetrations

- Failing coatings

- Irreparable window trim

- Distorted and non-original handrails

- Full-length cracks in roof panels

- One panel separating after blasting

- Moisture intrusion at joints

After Restoration

- All cracks welded and flush-finished

- Missing material infilled with A36 steel

- New cast window trim matched to originals

- Stainless-steel handrails fabricated to historic design

- New structural support frame and weldments installed

- Full coatings system applied for coastal conditions

- New glazing installed and documented

- Structure released and finish painted

“Allen Architectural Metals, which McBeth Called one of the nation’s premier cast iron restoration companies, handled the restoration of the lantern at its shop in Talladega, Alabama.”

Excerpt from “Foggy dawn operation returns historic lantern to this beloved Oregon Lighthouse,” by Lori Tobias, published in The Oregonian, August 2025.

Read the full article at: https://www.oregonlive.com/travel/2025/08/foggy-dawn-operation-returns-historic-lantern-to-this-beloved-oregon-lighthouse.html